Two Exhibits: Veiled Meanings, Fashioning Jewish Dress and Contemporary Muslim Fashions

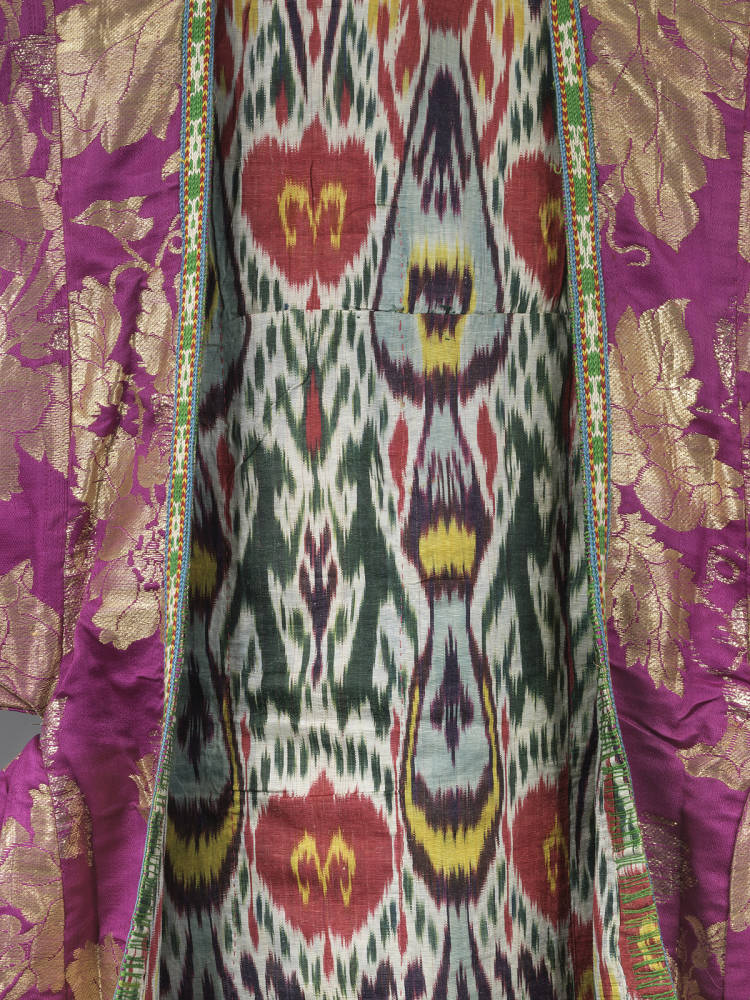

Woman’s coat (detail). Bukhara, Uzbekistan, late nineteenth century. Brocaded silk, ikat-dyed silk and cotton lining. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Photo © The Israel Museum, Jerusalem by Mauro Magliani

The first comprehensive US exhibition is drawn from the Israel Museum’s world-renowned collection of Jewish costumes. Veiled Meanings: Fashioning Jewish Dress from the Collection of The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, shown at San Francisco's Contemporary Jewish Museum displays more than 100 articles of clothing spanning the eighteenth to twentieth centuries, drawn from over twenty countries across four continents. Arranged as complete ensembles or shown as stand-alone items, the sumptuous array of apparel offers an exceptional opportunity for American audiences to experience many facets of Jewish identity and culture through rarely seen garments.

Married woman’s ensemble. Salonika, Ottoman Greece, early twentieth century. Silk, brocaded and ribbed, cotton lace, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem; Photo © The Israel Museum, Jerusalem by Mauro Magliani

The extraordinary range of textile designs and clothing on display illuminates the story of how diverse global cultures have thrived, interacted, and inspired each other for centuries. The featured clothing represents Jewish communities from Afghanistan, Algeria, Denmark, Egypt, Ethiopia, Germany, Georgia, Greece, India, Iran, Iraq, Iraqi Kurdistan, Israel, Italy, Libya, Morocco, Poland, Romania, Tunisia, Turkey, the United States, Uzbekistan, and Yemen, with the majority of pieces originating from North Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia. Foregrounding color, texture, function, artistry, and craftsmanship, Veiled Meanings offers an incisive and compelling examination of diversity and migration through the lens of fashion.

The Israel Museum is the repository of the most comprehensive collection of Jewish costume in the world. Its holdings provide a unique testimony to bygone communities, to forms of dress and craft that no longer exist, and to a sense of beauty that still has the power to enthrall. This touring version of The Israel Museum’s original exhibition Dress Codes, was developed for The Contemporary Jewish Museum and The Jewish Museum in New York, which are the only two venues to exhibit Veiled Meanings in the United States to date.

“The CJM is pleased to present the first West Coast showing of this magnificent exhibition of costumes and textiles made and worn by people of Jewish heritage all around the world,” says Lori Starr, Executive Director, The CJM. “Certainly, visitors will delight in the beauty and craftsmanship of these garments, but will also truly be struck by both the vast diversity of the Jewish global diaspora and by how much commonality there is in the dress of other world religions and cultures. With the deYoung’s exhibition, Contemporary Muslim Fashion, on view at the same time, San Francisco is going to be a destination this fall for anyone interested in what clothing tells us about culture.”

Veiled Meanings offers an opportunity to consider the language of clothing in all its complexity — to what extent our choice of dress is freely made and how our surroundings affect our decisions. The exhibition focuses on how clothing balances the personal with the social, how dress traditions distinguish different Jewish communities, and how they portray Jewish and secular affiliations within larger societal and global contexts.

Historical, geographic, social, and symbolic interpretations will be included within the context of four thematic sections:

Exposing the Unseen, the largest section in the exhibition, magnifies the fine and often hidden details of clothing, the many layers and extraordinary craftsmanship that comprise an ensemble, and the symbolic embellishments that define a garment’s purpose. Exquisite linings, embroideries worn beneath outer garments, and other hidden components attest to the importance accorded to beauty and fine craftsmanship even when those details were enjoyed only by the wearer. Even some aspects of clothing visible to all were appreciated only by those familiar with local motifs and their meanings. Visitors will be able to view the lavish ikat lining of a Bukharan coat; embellished bodices worn by Baghdadi Jews in Calcutta; and men’s sashes from Morocco and Iraqi Kurdistan. Also examined is the tension between the desire to reveal and the dictum to conceal. Paradoxically, these often elaborately crafted modesty garments drew attention to the physical attributes they were intended to obscure.

Through the Veil focuses on veils and wraps worn by Jewish women in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Uzbekistan, demonstrating the influence of local Islamic culture on Jewish dress. While covering a woman’s body and face, veils and wraps revealed important aspects of her identity, such as religion, status, or place of origin. Wraps of this type were once a universal custom in parts of the Middle East and Central Asia, and remain prominent within many Muslim communities today. A unique example of a wrap worn by Jews exclusively is the Herati chador. The chador originated from Muslim Iran and was brought to Afghanistan by Mashhadi crypto Jews that fled from Iran to Herat following persecution at the beginning of the nineteenth century. In Herat this became identified with Jewish women differentiating them from the Muslim women who wore the burka. The extent to which a woman is concealed by her clothing remains a timely issue.

Articles of clothing used in tribute are included in the section entitled Clothing that Remembers. Garments often serve to perpetuate the memory of the dead — at times after being repurposed or redesigned to fulfill this new role — as in the transformation of lavishly embroidered Ottoman Empire bridal dresses into commemorative Torah ark curtains. In other cases, the memory enshrined in clothing is personal, marking a rite of passage. For example, until the mid-twentieth century, it was customary in Tétouan, Morocco, for a bridal couple to wear their shroud tunics under their wedding clothes, in order to recall the transience of life.

The final section, Interweaving Cultures broadly examines the migration of Jewish communities and the effects of acculturation. Jewish costume often transmitted styles, motifs, crafts, and dress-making techniques from one community to another as Jews migrated across Europe, Asia, and the Americas. The ensembles presented also reflect the political and social changes that occurred in the regions where Jews settled. From Spain to Morocco, from the Ottoman Empire to Algeria, from Baghdad to Calcutta, clothing styles developed from the melding of imported and local fashions, materials, and craftsmanship.

The costumes displayed here reveal how clothing from distant locations and cultures influenced both Jewish fashion, and non-Jewish dress, frequently resulting in innovative and often eclectic creations. Wherever they settled, the Jewish people usually wore similar dress to that of the surrounding society, making this collection an opportunity to present a diverse array of global encounters. As modernization began to take hold, handcrafted fabrics were frequently used along with industrially produced textiles — or were replaced by them. A highlight of this section is an Iranian deep purple silk, velvet, and cotton outfit from the early twentieth century that incorporates elements from the Parisian ballet — a short and flared ballet-like skirt is paired with matching pants to ensure modesty.

Within Interweaving Cultures, a vast subgroup of garments celebrates the diversity of clothing worn in Jewish marriage ceremonies around the world. One or two generations ago, a rich variety of color and composition often comprised the ceremonial dress of Jewish brides and grooms. Celebrating the confluence of multiple time periods and traditions, this subsection features a brocaded silk sari worn by a bride in India’s mid-twentieth century Bene Israel community; the undergarments of a trousseau from Rome; the colorful “Great Dress” originating from Spain and worn by Jewish women in coastal Morocco; and a 1947 wedding gown from New York made of silk satin and embellished with early nineteenth-century Burano lace and pearls, among others.

Ido Bruno, Anne and Jerome Fisher Director of the Israel Museum, Jerusalem says of the exhibition, “Our interdisciplinary collection assembled over decades brings to life communities that have been scattered all over the world and no longer exist. The story of the Jewish wardrobe allows us to understand the origins and the narration of Jewish creativity, as well as the ways that communities differ from and integrate with their neighbors more broadly, which is what makes this exhibition so relevant to audiences worldwide.”

The Veiled Meanings: Textile Lab is an educational annex to the exhibition that will be located in The Museum’s Stephen and Maribelle Leavitt Yud Gallery. The Textile Lab delves into the craftsmanship and embellishment of the fabrics and explores local connections to the clothing traditions. The space offers opportunities to weave, to play with draping and dressing, and to embroider. It features a listening station with interviews of community members from the regions represented in the exhibition, a community-driven photo montage, and pop-up programs with textile artists, musicians, and Jewish community members from Middle Eastern and North African heritage.

More Articles

- National Archives Records Lay Foundation for Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI

- Attorney General Merrick B. Garland Delivers Remarks at the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York

- Nichola D. Gutgold - The Most Private Roosevelt Makes a Significant Public Contribution: Ethel Carow Roosevelt Derby

- Women's Health and Aging Studies Available Online; Inform Yourself and Others Concerned About Your Health

- Oppenheimer: July 28 UC Berkeley Panel Discussion Focuses On The Man Behind The Movie

- "Henry Ford Innovation Nation", a Favorite Television Show

- Ferida Wolff's Backyard: Fireworks Galore!

- Julia Sneden Wrote: Going Forth On the Fourth After Strict Blackout Conditions and Requisitioned Gunpowder Had Been the Law

- Julia Sneden Wrote: If The Shoe Fits ... You Can Bet It's Not Fashionable

- Jo Freeman Reviews: Gendered Citizenship: The Original Conflict Over the Equal Rights Amendment, 1920 – 1963