Assisted Dying provides a fast ride on the highways of the Gold Coast. It is a good, rather riveting read. Equally important, like Agewise, this mystery would make a terrific book group choice, a vehicle for discussing different aspects of American culture and how they influence what Gullette calls “the decline narrative.”

©2011 Jill Norgren for SeniorWomen.com

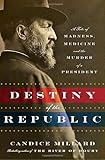

Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine and the Murder of a President

by Candice Millard, © 2011

Published by Doubleday/Division of Random House; Hardcover: 260 pp

Lovers of history will find Destiny of the Republic a most interesting book. Author Candice Millard has done a superlative job of research and organization, making the book a kind of literary trifecta. She manages to balance the separate but interlocking histories of President James A. Garfield, his assassin Charles Guiteau, and the famous inventor, Alexander Graham Bell, whose efforts to help save President Garfield were defeated by an incompetent doctor.

Millard gives us a distressingly vivid picture of Guiteau, a delusional and damaged soul who failed at everything he ever undertook, but nonetheless regarded himself as someone destined for greatness.

Garfield, on the other hand, was a man who came from extreme poverty, but by virtue of a questing mind and great self-discipline, achieved success in everything he touched. A brilliant scholar and orator, he was also solidly grounded in a good marriage and a vibrant family life. He and his wife, Lucretia, had six children, two girls (the eldest daughter died at age three) and four lively boys.

In 1876, Garfield, whose mind apparently never stopped that questing, took his young family to see the United States Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Millard takes advantage of this fact for a delightful aside involving a young immigrant from Scotland named Alexander Graham Bell who came to the Exposition to demonstrate his new invention, the telephone. Through a series of mishaps, his invention was presented in an out-of-the-way spot, and would have been entirely overlooked had not Dom Pedro, the Emperor of Brazil, also been in attendance. The emperor, “a passionate promoter” of all scientific advances, dragged the judges to Bell’s exhibit, where Bell astounded them all by reciting Hamlet’s “To Be or Not To Be” soliloquy from a different room, through the telephone.

Millard also mentions that during the Exposition, British doctor Joseph Lister delivered a lecture about his work to establish new and important procedures for antisepsis. He spoke to a large crowd that included many of America’s best-known surgeons and doctors, but his lecture was largely ignored because of its “crackpot ideas.” Those ideas, which involved things like the sterilizing of surgical tools and washing of hands, had been recognized and implemented in Europe as being effective against infection. Had those American doctors been less hidebound or provincial, it is likely that Garfield’s death, some five years later, needn’t have happened, because the true cause of his death was not the gunshot, but septicemia.

Garfield’s assassination occurred at a time in US History which in many ways sounds eerily like our own. After the Civil War, the Republican Party had devolved into two factions. “The Stalwarts” were extremely conservative and resistant to change, and wanted no interference in the spoils system of giving federal jobs through patronage. They were also opposed to any reconciliation with the South, following the Civil War.

“The Half-Breeds,” also Republicans, were progressive reformers, interested hiring merit-based civil servants, and dealing with the corruption in Congress. They also advocated reconciliation with the South. Garfield, a Civil War veteran, was familiar with the misery and destruction of war. He was an ardent Abolitionist, and fought bravely in the war, but in its aftermath, he recognized the need to heal the nation by reaching out to the South.

As a result of the polarity between Stalwarts and Half-Breeds, the Republican nominating convention of 1880 soon was in stasis, with neither side able to give its candidate enough votes to secure the nomination. Senator James Blaine, a "Half-Breed” who had been chasing the Presidency for many years, was nominated by a less-than-inspiring delegate from Michigan who gave a mediocre speech, and even misidentified Blaine’s middle initial as S, not G.

Roscoe Conkling, senior senator from the state of New York, led the Stalwarts. He was a ruthless power-broker who, at the convention, nominated Ulysses S. Grant in a wildly emotional speech that whipped the convention crowd up into something close to hysteria.

Next to speak was Senator James Garfield of Ohio. He had agreed to nominate John Sherman, brother of General William Tecumseh Sherman. Garfield, who had spent seventeen years in Congress and was known to be one of its best orators, delivered a nominating speech that was a masterpiece of reason and calm, the complete and well-planned opposite of Conkling’s rant. When, at its end, he asked: “And now, gentlemen of the Convention, what do we want?” an answer was shouted out by someone in the crowd, but the name offered was not Sherman’s. It was: "We want Garfield!" That cry brought a wave of support, and despite Garfield’s initial refusal and dismay, he soon found himself to be the nominee for a position he had not sought.

Life in the White House was very different from the Garfields’ happy life on their farm. For one thing, the White House was falling apart, with rotting wood and peeling paint and rats in residence, as well as muddy, untended grounds. Lucretia, Garfield’s wife, came down with a severe case of malaria, not at all uncommon given Washington’s swampy environment. She soon had to be packed off to the Jersey shore, in hopes of improvement that the fresh sea air could (and did) bring.

Washington, in those days, was a wide-open place. The White House held public calling hours from 10:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. Monday through Friday, and security was very casual. The President was known often to stroll alone through the city.

Charles Guiteau, ever more delusional, showed up very shortly after Garfield’s election, presenting himself at the calling hours. He began haunting the halls to waylay anyone who would listen to him, thrusting on the listener a copy of a speech he had written in praise of Garfield during the campaign. He considered himself to have been a major influence in Garfield’s election, and expected to receive the post of Ambassador to Paris. It wasn’t very long before Garfield’s personal secretary sized him up and sounded the alarm, asking the staff to keep Guiteau away from the halls and reception rooms.

Candice Millard’s account of the stalking that lead up to Garfield’s assassination on July 2, 1881 is deeply disturbing. Accustomed as we have become to the creepiness of assassins who hunt and track their targets, from Lee Harvey Oswald to James Earl Ray to Sirhan Sirhan, it is no less chilling to envision the deranged Charles Guiteau lurking in the shadows as he watches Garfield moving about Washington, DC.

The fatal shots were fired in the railroad station as Garfield was about to embark on a vacation at the Jersey Shore, to rejoin his beloved Lucretia. Bystanders swiftly subdued Guiteau, who was taken to jail, the enormity of his madness evidenced by a letter in his pocket. It was addressed to General Sherman, and asked that Sherman order his troops to take possession of the jail at once, presumably for Guiteau’s protection.

The shots that hit Garfield were not fatal. In fact, there is every reason to expect that he might have lived, had his doctors followed Dr. Lister’s simple procedures of sterilizing equipment. Instead, they probed Garfield’s back repeatedly, and agonizingly, during several weeks as they tried to find the bullet, using dirty probes and unwashed hands. As the wounds became infected and the President’s fever rose, reports were posted announcing that Garfield was definitely recovering, and that the “healthy pus” that formed was a good sign. His chief doctor, a doctor named Doctor (his real first name) Bliss, had simply stepped in and assumed Garfield’s care, and brooked no dissent to his treatment.

Enter Alexander Graham Bell, whose fertile mind realized that he could make a device he called the “induction balance” which would be able locate the lead bullet through electric sound. He set to work feverishly, and managed to receive permission to try the device, although Dr. Bliss would not allow him to scan Garfield’s left side, inasmuch as the good Dr. Doctor Bliss had determined that the bullet must be on the right. Alas, Bell could get no reading, and had to admit defeat despite being certain that his device would work. After Garfield’s death, an autopsy proved indeed that the bullet had lodged on the left side, below the pancreas, and had Bell been allowed to search there, he most certainly would have found the bullet. In fact, Bell’s induction balance was used successfully to find bullets in wounds, for several years before the invention of the X-ray.

Near to the end, Garfield asked to be taken to New Jersey, to be by the sea. A special, 4-car train was obtained, and finally, on September 6th, Garfield was carried aboard. The trip to New Jersey may be reminiscent for anyone who remembers the pictures of FDR’s funeral train, as at every station that Garfield’s train passed, crowds of people stood, heads bowed, women weeping. When the train reached Elberon, NJ, it was found that the engine wasn’t strong enough to pull the cars up the hill to the seaside cottage, despite the fact that two thousand people had worked until dawn, laying track to the door. Two hundred men then ran forward to help, and manually pulled the three coaches up the hill.

President Garfield died on September 19, 1881.

Charles Guiteau was executed on June 30, 1882, despite his family’s plea for mercy on grounds of insanity.

This reviewer’s recounting of the facts that Millard so carefully lays out gives no more than a small hint of the author’s sensitive, detailed account of Garfield’s murder. The book goes onto my highly recommended list, with no reservation.

Illustration: President Garfield with James G. Blaine after being shot by Charles Guiteau. From Wikipedia.

©2011 — Julia Sneden for SeniorWomen.com

More Articles

- A Proclamation on National Stalking Awareness Month, 2024 From Joseph R. Biden Jr.

- Sheila Pepe, Textile Artist: My Neighbor’s Garden .... In Madison Square Park, NYC

- Jo Freeman Reviews: The Moment: Changemakers on Why and How They Joined the Fight for Social Justice

- Office on Violence Against Women Announces Awards to 11 Indian Tribal Governments to Exercise Special Domestic Violence Criminal Jurisdiction

- Attorney General Garland Delivers Remarks at the National Association of Attorneys General

- Women's Congressional Policy Institute: Weekly Legislative Update September 13, 2021: Bringing Women Policymakers Together Across Party Lines to Advance Issues of Importance to Women and Their Families

- Jo Freeman Reviews From Preaching to Meddling: A White Minister in the Civil Rights Movement

- Jo Freeman Reviews It’s In The Action: Memories of a Nonviolent Warrior by C. T. Vivian with Steve Fiffer

- The Scout Report: Civil Rights Toolkit; Be All Write; Plants Are Cool, Too; NextStrain; Women'n Art; 500 Years of Women In British Art

- The Scout Report: Penn and Slavery Project, Robots Reading Vogue, Open Book Publishers, Black History in Two Minutes & Maps of Home