Culture Watch Book Reviews — Against All Odds: Resisting Oppressive Cultures, Political Violence and Natural Catastrophe

Editor's Note: Nicholas Kristof's column of April 12, 2015 ... Smart Girls vs. Bombs

"So instead of pummeling each other on foreign policy, let's look for lessons learned. Surely one of them is that to counter terrorists, sometimes a girl with a book is more powerful than a drone in the sky."

— Reviewed by Serena Nanda

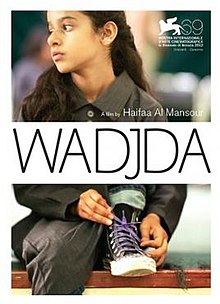

Wadjda, a Saudi Arabian and German film

Written and Directed by Haifaa al-Mansour

On DVD, Razor Film Produktion, 2012

Hold Tight, Don't Let Go: A Novel of Haiti.

By Laura Rose Wagner

Published by Amulet Books; 272 pages. 2015

I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban

By Malala Yousafzai with Christina Lamb

Published by Little Brown/Hachette; 289 pages. 2013. (Young Readers Edition, with Patricia McCormick, 2014)

Lost Kingdom: Hawaii's Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and America's First Imperial Adventure

By Julia Flynn Siler

Published by Grove Press; 296 pp, text with added Notes and Sources, 2012

The stories reviewed feature young girls and women who demonstrate persistence and courage in fighting against extraordinarily difficult circumstances in four very different societies. Each narrative is deeply engaging and furthers our understanding of how the subtext of politics and culture impacts individual lives.

Wadjda is the story of a quietly but ingeniously, rebellious 11 year old girl in contemporary Saudi Arabia, determined to buy and ride a bicycle, one of many activities restricted for women. It is no mean directorial feat that this simple tale, which has its roots in the deeply misogynist and rigid Wahabi Islamist Saudi culture, evokes smiles and laughter. Saudi Arabian women cannot leave home unaccompanied by a male relative, are not permitted to drive, are publicly policed for immodest dress, are sex segregated even in elementary school and are subjected to many other culturally based restrictions. It is the subtle revealing of this restrictive culture, and its many contradictions, that makes close viewing of Wadjda so important and demonstrates the courage and perceptiveness of its (female) director.

Pay close attention to the details of the film to grasp the serious story beneath the great charm of its characters and the inventiveness of the central plot. For example, Wadjda's repressive school principal forbids her rebellious act of wearing high top sneakers, but a close look reveals that the principal herself wears fashionable Western style high heeled shoes underneath her chador. This cultural contradiction is only one of many, illustrated also by Wadjda's mother, whose sexy beauty, fashionable dress, and social machinations, are part of her campaign to prevent her husband from seeking a second wife. Like the book reviewed below, the suspense of how it will all end engages us right up until the final scenes.

Hold Tight Don't Let Go immediately compels attention by its colorful cover which reminds us of contemporary Haitian art. The book is subtitled A Novel of Haiti but to anyone at all familiar with that country, the deep authenticity of the story and its characters shines through. This should not surprise us; its author, Laura Wagner is a cultural anthropologist who has lived in Haiti for three years and was there when the disastrous earthquake of 2010 hit the island. As cultural anthropologists do, she learned the language (which she seamlessly inserts into the novel), formed close friendships on the island, and clearly understands both the context of its politics and the nuances of its culture.

The opening chapter details the devastating impact of the earthquake on its central character, a 17 year old girl, Magdalie, whose whole life changes as her home collapses, killing Manman, the woman who became her beloved mother when her real mother died in her infancy. Manman brought her up in Port-Au-Prince with her own daughter, Nadine, and the girls are as close as twins, a closeness that becomes her emotional lifeline in the earthquake’s aftermath. Magdalie and Nadine move in with her uncle in a camp established by a Western NGO for earthquake survivors, but another emotional disaster strikes when Nadine is granted a visa to America, where she goes to live with her father. Now Magdalie is truly on her own, surviving only on the illusion that someday Nadine will send for her to come to Miami.

Forced now by her poverty to leave school, Magdalie desperately makes one unsuccessful effort after another to survive. We are in awe of her courage, especially her decision to refuse to sink to selling sex, which for many young girls and women is the only way of feeding themselves and their families. Most of us reading this novel will, thankfully, never experience the extreme disaster of an earthquake or the dire poverty of Haiti: it is to the author’s great credit that in spite of this distance we are moved to complete empathy and identification with the novel’s main character.

Violence of a different kind opens the memoir, I Am Malala, in which we encounter bravery that defies belief as Malala Yousafzai recounts her experiences as she and her father, against all odds, actively fight the Taliban for the right of girls to go to school in Swat, the tribal area of Pakistan in which they live. The memoir opens with a horrific incident: Taliban terrorists stop a school bus, peer inside and ask: "Who is Malala?" and then shoots her in the face. With the aid of Western doctors and, ambivalently, the Pakistani government, Malala survived and is now, of course, universally known as the youngest (14 year old) winner of the Nobel Peace prize.

My 11-year-old granddaughter, Charlotte, who read the young adult version of Malala's memoir, recommended I read the book and I am so glad I did. In spite of her incredible bravery, Malala describes her life as an ordinary girl, with a teenager's concerns about clothes, school cliques, and getting good grades. In her somewhat matter of fact, and even humble style, she reminds us of Magdalie in Haiti, who also sees herself as ordinary and who shares Malala's view that education for girls is their best hope.

I Am Malala is most engrossing when Malala writes in her own words about her family, her friends, her everyday life, and especially her relationship with her father, but the descriptions of Pakistani history and politics, presumably written by the co-author, are clearly an essential context for her story. The Swat Pushtun were more vulnerable to Taliban repression and violence because their culture, while patriarchal and even misyogynst, was less restrictive for women than the dominant culture of Pakistan today. Many Pakistanis do not share the admiration for Malala she so clearly deserves but her activism, and her survival, against all odds, makes her memoir a compelling read for both adults and young adults throughout the world.

Pages: 1 · 2

More Articles

- Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco Deliver Remarks at ATF’s Inaugural Gun Violence Survivors’ Summit

- Hope: A Research-based Explainer by Naseem S. Miller, The Journalist's Resource

- Justice Department Files Statement of Interest in Case on Right to Travel to Access Legal Abortions

- Women's Health and Aging Studies Available Online; Inform Yourself and Others Concerned About Your Health

- Justice Department Deputy Attorney General Lisa O. Monaco Delivers Remarks on Charges and New Arrest in Connection with Assassination Plot Directed from Iran

- "Henry Ford Innovation Nation", a Favorite Television Show

- Ferida Wolff's Backyard: Fireworks Galore!

- Attorney General Merrick B. Garland Statement on Supreme Court Ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization

- New York Historical Society Presents Exhibition Honoring Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg

- Jo Freeman Reviews Mazie's Hirono's Heart of Fire: An Immigrant Daughter's Story