Why the ‘Skills Gap’ Doesn’t Explain Slow Hiring

Mankato, Minnesota’s historic downtown. Communities across America want to better connect workers looking for jobs and employers looking to hire. © The Pew Charitable Trusts

This is the first part of the Stateline* series Help Wanted: Why Willing Workers Aren’t Filling Open Jobs, which was originally published earlier this year.

Le Sueur, Minn. — Customers can’t get enough of Cambria's quartz countertops, and the million-square-foot production facility here is racing to keep up. Under bright lights and high ceilings, churning machinery fuses quartz crystals into heavy slabs and polishes them until they shine.

This facility is short 40 production workers. It took months to find all the workers for a new assembly line added earlier this year — even after Cambria boosted entry-level wages from $16.66 to $18 an hour. The labor shortage is costing the company some $3.8 million per month, said Marty Davis, the company's president and CEO.

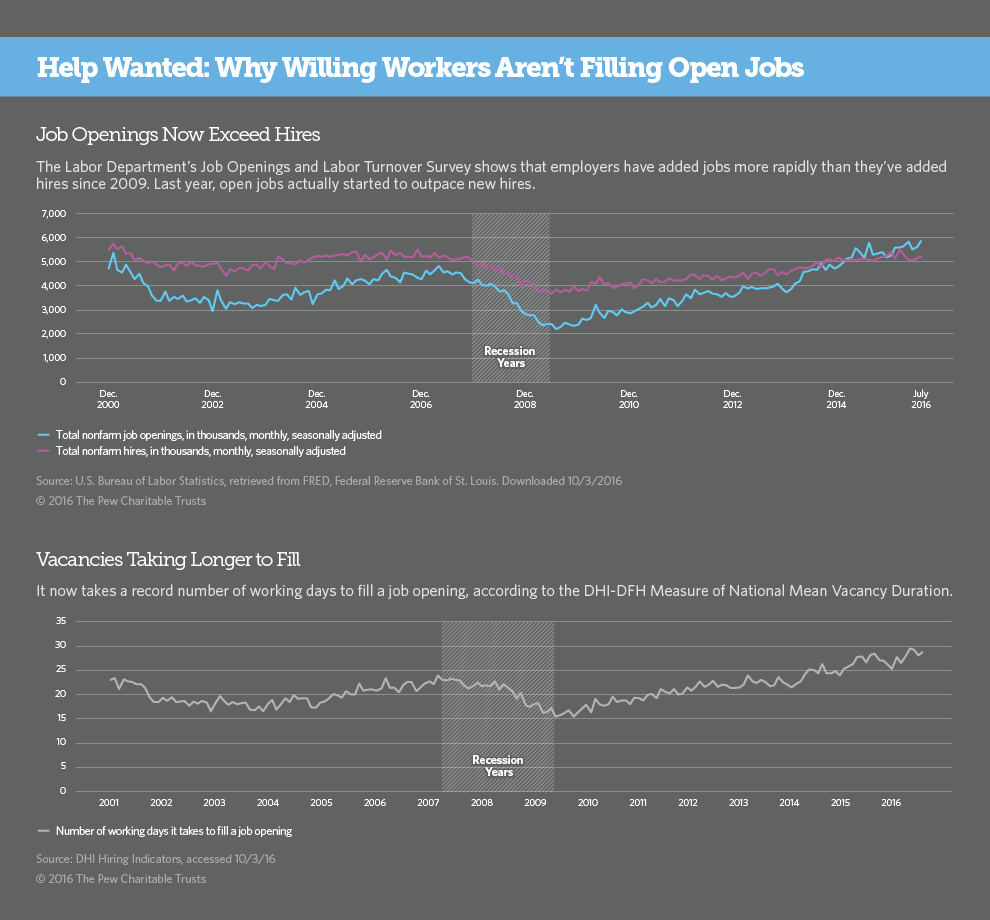

Employers across the country, from manufacturers in rural Minnesota to hospitals in New York City, are having trouble filling jobs. It now takes about 28 workdays to fill the average job vacancy, compared to about 24 days, on average, in 2007. The declining unemployment rate has made it more difficult for employers to find workers, but it's still tougher than it should be given the current jobless rate. Since the recession ended, the number of job openings has increased faster than the number of new hires.

The usual explanation offered by business and education groups is that too few Americans have the right skills for the openings. The way to close this "skills gap," they say, is to improve job training and more closely align higher education to employment.

But this solution, promoted by politicians as the way to help workers left behind by globalization and automation — both major challenges for the country in the 21st century — is too simplistic.

Throwing more public dollars at education and training won’t be enough to connect willing workers to open jobs. In many places, employers are also setting wages too low, defining qualifications too narrowly, or not recruiting widely enough. Many people who are eager to work can’t because they lack transportation, or don’t have anybody to watch their children during the workday.

Besides, a lot of the open jobs that employers are struggling to fill right now don't require any education or training beyond high school.

"I think [the] 'skills gap' has run its course. It's overhyped and overrated," said Janice Urbanik of Partners for a Competitive Workforce, the umbrella organization for workforce efforts in the Cincinnati area. "I don't think it's the only factor, and to some extent it's not even the primary factor."

President-elect Donald Trump made restoring lost manufacturing jobs a centerpiece of his campaign. He says he will bring back jobs by cutting taxes, rolling back regulations and renegotiating trade deals. His position on education and training for displaced workers is unknown.

‘A Profound Social Challenge’

It's true that over the past 30 years, education and skill requirements for jobs have been rising, as a Pew Research Center study recently found. (The Pew Charitable Trusts funds both the Pew Research Center and Stateline.) But that long-term shift doesn't totally explain why jobs have been sitting open since the Great Recession ended. The US hasn't experienced the massive wage growth you'd expect from a shortage of workers, although wages did start rising last year. Many economists say that if there were a shortage of workers, wages would be going up more.

They say the lack of wage growth proves the US has a demand problem — not enough good jobs — rather than a supply problem — not enough skilled workers. The idea that all we need to do is train workers is "fundamentally an evasion of a profound social challenge," former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers said during a panel discussion hosted by the Brookings Institution last year in Washington, D.C.

"Training is very important and indeed necessary," Summers told Stateline. "But it is not sufficient to meet either the near-term challenge of assuring demand and preventing recession or the longer-term challenge of the structural loss of jobs for less-skilled workers."

More Articles

- Women's Congressional Policy Institute; Weekly Legislative Update, July 22, 2024; Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, Agriculture, Nutrition Assistance, Child Care, Women-owned Business Programs at the Small Business Administration.

- National Institutes of Health: For Healthy Adults, Taking Multivitamins Daily is Not Associated With a Lower Risk of Death

- Women's Congressional Policy Institute: Ensuring Equity for Women Veterans at the VA, Missing Children’s Assistance Reauthorization Act of 2023

- November 1, 2023 Chair Jerome Powell’s Press Conference on Employment and Inflation

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: Something’s Got to Give by Governor Christopher J. Waller

- Women's Health and Aging Studies Available Online; Inform Yourself and Others Concerned About Your Health

- Jerome Powell's Semiannual Monetary Policy Report; Strong Wage Growth; Inflation, Labor Market, Unemployment, Job Gains, 2 Percent Inflation

- February’s Hot Data Releases: Governor Christopher J. Waller, Federal Reserve Board Frames a Few of the Issues Around Inflation and the Economic Outlook

- "Henry Ford Innovation Nation", a Favorite Television Show

- Remarks by President Biden on American Rescue Plan Investments; September 02, 2022, South Court Auditorium Eisenhower Executive Office Building