Renewing Respect for Language: The Subjunctive Is a Governor of the Consciousness That Uses It

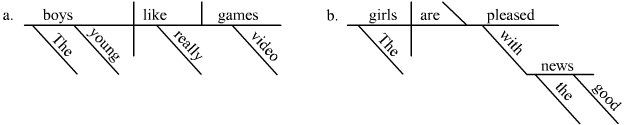

An example of the Reed Kellogg sentence diagramming system; Wikimedia Commons

In my teens I came to the realization that without words we could not actually think. Feel, emote, react — of course, but it takes words to think.

My father was a perfectionist. A musician and writer, he did his best to reorder his world to an ideal of regularity and esthetic standards. That included his growing daughter's handling of the English language.

I recently heard a remarkable lecture by a non-native speaker (and teacher) of English about the subjunctive. Like many of my coevals, in elementary school we were given the barest elements of English grammar. It wasn't until I was exposed to years of French and four of Latin that I even understood what the subjunctive is. One reason I didn't need to was that if my father overheard me forget it, he would be sure to remind me: If it were, not if it was. I wasn't a rebel, so I did my best to remember.

Then this discussion provided the idea that we who value the power of language must never forget: the subjunctive is a governor of the consciousness that uses it. It actually is an enabler for both speaker and listener without which most of us would never understand half of what we learn.

The lecturer is a Vietnamese refugee. Having mostly grown up in the United States, he is at home with the possibilities, with the alternative realities with which the concept of the subjunctive makes us conversant. Most of my youthful willingness to learn correct grammar and something of the nature of syntax was sort of a matter of learning to please my father and my English teachers. Analysis of what is implicit in those formalities had to wait for my understanding of complexities of character and psychology to develop. I grew up speaking English and remained virtually unaware: it was the lack of respect owing to complete familiarity.

Imagine what it must have seemed like to a boy when he asked his father what he thought a dreadful experience (the strafing death of several relatives on a bus) might have been like. When he asked what his father might imagine life would be had this not happened, had his mother and other relatives not perished on that bus he and his father had missed. In Vietnamese all his father could reply was that (in effect) what is is. Period.

What was was, and that's all there is to it. What will be will be. The language doesn't allow for speculation, for referral to the past in any way but to the facts of what occurred. Nothing is alterable by the emotions or opinions of the speaker because there is no way to express those suppositions or wishes or imaginings. The future can't really be linked to past memories — only to past events. Speculation can't be expressed because the language itself doesn't allow it!

If only I had figured this out while I was teaching ordinary high school students. If only I thought there were time enough time to elaborate on the implications of this notion. All by itself, it makes the study of history into a new discipline.

©2015 Joan L. Cannon for SeniorWomen.com

More Articles

- National Archives Records Lay Foundation for Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI

- Nichola D. Gutgold - The Most Private Roosevelt Makes a Significant Public Contribution: Ethel Carow Roosevelt Derby

- Oppenheimer: July 28 UC Berkeley Panel Discussion Focuses On The Man Behind The Movie

- Selective Exposure and Partisan Echo Chambers in Television News Consumption: Innovative Use of Data Yields Unprecedented Insights

- Julia Sneden Wrote: Love Your Library

- "Henry Ford Innovation Nation", a Favorite Television Show

- Julia Sneden Wrote: Going Forth On the Fourth After Strict Blackout Conditions and Requisitioned Gunpowder Had Been the Law

- The Stanford Center on Longevity: The New Map of Life

- Jo Freeman Reviews: Gendered Citizenship: The Original Conflict Over the Equal Rights Amendment, 1920 – 1963

- Jo Freeman Writes: It’s About Time