Milwaukee’s Civil Rights Legacy by Jo Freeman

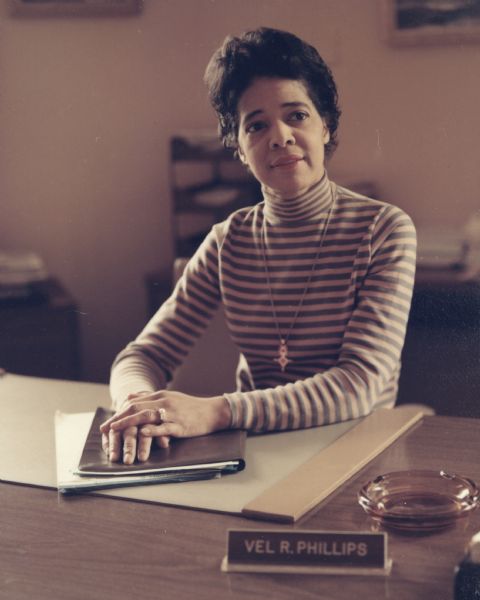

As I walked the streets of Milwaukee, viewing some elegant old churches, I thought about its civil rights legacy. One street is named Dr. M.L.King Jr. Drive, though I don’t think Dr. King ever spoke in Milwaukee. Another is named Vel R. Phillips Ave. A Milwaukee native, she was a multiple first. The first Black woman who: graduated from U. Wisconsin Law School, elected to the city council, judge, elected Secretary of State, served on the Democratic National Committee. She was also active in the NAACP, leading open housing marches and getting arrested.

Shortly after she died in 2018, N. 4th St. was renamed in her honor. That’s why the official address of the Fiserv Forum, where the Republican convention was held July 15-18, is 1111 N. Vel R. Phillips Ave.

Less well known in Milwaukee, but better known to civil rights activists, is Father James Groppi, also a Milwaukee native. A few years after ordination in 1959, he was assigned to St. Boniface Church in the segregated Black community of north Milwaukee. There he developed an empathy with the Black poor. He took several of his parishioners to the 1963 March on Washington and the 1965 Selma march. On June 4, 1965 he and four other clergymen were arrested when they blocked a school bus. They were among 50 demonstrators protesting the Milwaukee School Board’s policy of keeping Black children in separate classrooms in otherwise white schools. The Board was under court order to bus children from overcrowded Black schools to white schools to foster integration, but it didn’t want to integrate the classrooms.

Groppi’s influence brought quite a few Catholic youth, Black and white, into the civil rights movement. Ten of them worked with SCOPE, SCLC’s 1965 summer project. Fr. Groppi drove seven to Atlanta, where they helped set up for orientation. One of those was his future wife. Fr. Groppi couldn’t stay in the South for the entire summer. But he spent his two-week vacation in August in Bullock County, AL working with those he had brought South in June. St. Boniface Church was razed in 1975 to make way for a new high school. Fr. Groppi was not reassigned to an African-American parish. Instead, he married in 1976 and became a bus driver. Always an activist, he led fair housing marches across the 16th St. Viaduct, which spans the Menomonee River Valley. This bridge separated north Milwaukee, where poor Blacks lived, from south Milwaukee, home of middle-class whites. James Groppi died of brain cancer in Milwaukee on November 4, 1985. In 1988 the Viaduct was renamed the James E. Groppi Unity Bridge.

Then there’s America’s Black Holocaust Museum, further north into the (still) poor Black neighborhoods of Milwaukee. It’s a purely private endeavor. Founded by James Cameron in 1988, the ABHM was inspired by the Holocaust memorial museum in Israel. It interprets the Black experience in the US as an ongoing series of mass atrocities. Cameron teamed up with philanthropist Daniel Bader to open the Museum. After Cameron died in 2006, the physical museum closed due to lack of funding. The museum went online as a virtual museum in 2012. After additional funding was secured, it reopened in 2022, but is only open a couple days a week. One of its seven History galleries is about the Civil Rights Movement – nationally, not Milwaukee.

Copyright © Jo Freeman 2024