Jo Freeman Reviews: No Common Ground: Confederate Monuments and the Ongoing Fight for Racial Justice

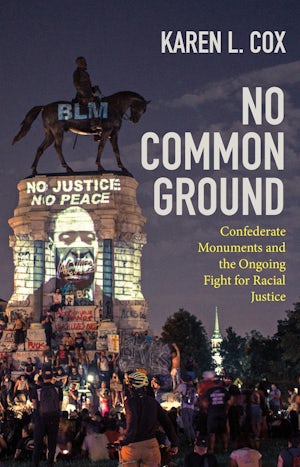

NO COMMON GROUND: Confederate Monuments and the Ongoing Fight for Racial Justice

By Karen L. Cox

Published by Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press

206 pages plus 14 photographs

This is a timely book. What to do with statues of Confederate soldiers has been much in the news lately. As the author points out, however, this is just the latest twist in a story that began after the Civil War.

Those who suffer defeat, be they Presidents or populations, deal with downfall in different ways. Denial is one way. Simply flip defeat on its head and claim victory. You might not get the concrete benefits of an actual victory, but you can get the psychological ones.

The white South admitted to only military defeat. To claim a moral victory, it invented the Lost Cause, which saw the War as an heroic attempt of a noble people to leave a union that only wanted to exploit its wealth. Believers insisted that the reason for the War was states’ rights, ignoring the fact that the Secession Ordinances declared it to be slavery.

The Lost Cause evolved into a civil religion, with the myths, symbols and rituals typical of religions. Those Confederate monuments were the symbols, icons of Southern white nobility, representations of a heroic Southern culture.

The development of this culture, especially its objects of veneration, owes a lot to women. While the War was still being fought, they created ladies' memorial associations (LMAs) to care for the Confederate dead. Bodies were returned from battlefields and interred in cemeteries closer to home. The LMAs erected headstones and decorated the graves annually. Care turned into celebration. The celebrations grew into Confederate Memorial Day, which was usually in the Spring, though not the on same date every place or every year.

The next step was to erect monuments to the soldiers’ memory. Toward this end the women had to raise funds, at a time when the South was, frankly, broke. That they succeeded is testimony to their skills, their connections and their determination. After white Democrats regained control of state and local governments, elected officials ceded public space to these monuments and also provided money for their maintenance. Veneration of the Confederacy became a state religion.

Relying on data from the Southern Poverty Law Center, Cox estimates that more than 1,700 monuments, markers and memorials to the Confederacy have been erected, of which between 750 and 800 are statues. While some have been erected every decade, the peak period was the two decades after the United Daughters of the Confederacy was founded in 1894. There was a boomlet during the 1920s and another one during the 1960s. The latter was both a response to the civil rights movement and part of the centennial of the Civil War.

Pages: 1 · 2