How It Works

Using one well-published telephone number (877-725-2552), anyone in the state can reach a registered nurse who picks up the line in less than three minutes – no telephone tree and no talking to robots. Most nurses who answer calls work part-time in local hospitals or clinics. All but a few answer phone calls from their homes.

After asking a series of questions, moving from most serious to least serious symptoms, a registered nurse uses medical algorithms and professional judgment to formulate a diagnosis. He or she then instructs the caller on what to do immediately and then often sets up an appointment with a local doctor. In a smaller number of cases, nurses tell callers to get to an emergency room as quickly as possible. "We always err on the conservative side," said registered nurse and program director Connie Fiorenzio.

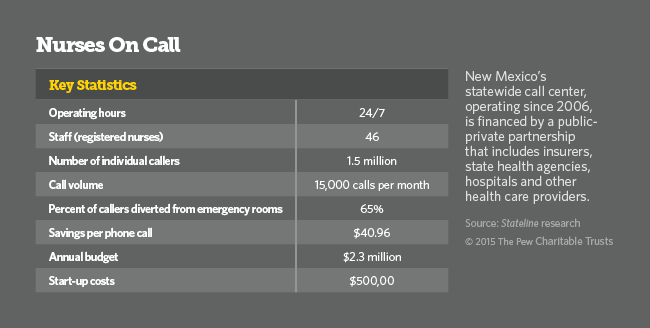

Financial support for New Mexico’s line comes from a public-private partnership that includes nearly every insurance carrier and managed care organization in the state, the state’s Medicaid and public health departments, the University of New Mexico's Health Sciences Center, Indian Health Services, and numerous hospitals, physician practices and community health centers across the state.

The statewide reach of New Mexico NurseAdvice line, as well as its close ties with the medical community, have made it particularly effective at stemming the spread of infectious diseases, the CDC's Koonin said.

During the H1N1 flu pandemic in 2009, for example, the line was able to keep thousands of people out of crowded emergency rooms and doctor’s offices where they were at risk of either spreading or contracting the virus.

Registered nurses were able to quickly determine whether callers' symptoms indicated they had the flu, or something else. In some cases, nurses would contact an on-call doctor to prescribe Tamiflu, saving the caller a trip to an overcrowded waiting room.

New Mexico's advice line stemmed the surges on hospitals and doctor's offices that other states across the country experienced. In other states, many of those who were illness-free panicked and went to the emergency room when they experienced any possible symptoms. In contrast, New Mexico's 24/7 nurses convinced many disease-free people to stay home, and gave clear instructions on how to avoid the contagion.

"When H1N1 hit, we were the resource," Fiorenzio said. "I got a call from the New Mexico Department of Health on a Friday night at 9:00. We were using a (flu-specific) protocol by the next morning and we’ve been responding in the same way ever since — whether it's hepatitis, listeria, salmonella or a water or restaurant problem."

When wildfires start burning in the summer, Fiorenzio said, the line is able to quickly pinpoint who is experiencing breathing problems so the state can set evacuation plans.

Beyond its public health benefits, NurseAdvice New Mexico stands out for other reasons. It has a 98 percent customer approval rating and a compliance rate of 85 percent, meaning callers heed the nurses' advice and either care for themselves at home, go to a doctor or go directly to a hospital based on the nurses' orders.

Importance of Being Local

Another distinction that led the CDC to hold up New Mexico's advice line as a model is the program is state-run and staffed by locals.

"It’s really important that the nurses who answer the line are familiar with the state’s health care system and its unique culture and lifestyles," said former state Sen. Dede Feldman, who sponsored $500,000 in start-up funding for the service in 2006. Feldman, a Democrat, said a major selling point was the call center would be state-based.

Lawmakers immediately saw the advantage, Feldman said. One lawmaker, she recalled, told a story about calling his own HMO advice line after he burned his eyes while peeling green chilis. He said a nurse in Nova Scotia answered the call and had no idea what a green chile was, much less how to help relieve the burning.

But New Mexico's aims in 2006 went beyond providing culturally sensitive health advice. Dr. Art Kaufman, chief of the community medicine department at the University of New Mexico, saw the project as a way to provide much needed health care advice to the state's large uninsured population. At the time, New Mexico had the second highest uninsured rate in the nation. He envisioned the advice line taking pressure off hospitals and doctors, particularly in the state’s remote regions.

He also believed the line was a way to help the state's large uninsured population find what medical professionals call "medical homes," a primary care provider or pediatric practice that coordinates a patient's care. When callers say they have no doctor, the NurseAdvice line sets up an initial appointment with a local doctor.

The line also provides respite for hard-to-find doctors who are willing to practice in remote parts of the state. "It has helped them avoid burn out and stay in their jobs longer," Feldman said.

New Mexico's success at launching its first-in-the-nation, public-private advice line was due in large part to a profound need for greater access to health care. With too few doctors and too little insurance coverage, it was obvious to everyone that something had to be done, Feldman said.

In 2006, New Mexico’s then-Democratic Gov. Bill Richardson tried and failed to enact a major health care reform law aimed at expanding insurance coverage. "While that was going on," Feldman said, "we snuck this one through. It was low-tech and straightforward. It would make a difference on the ground."

Dr. Bart Schmitt, a pioneer in the field of telephone triage, gives Richardson much of the credit for the NurseAdvice line. “Bill Richardson pulled together the stakeholders — big hospitals, the university and insurance companies — and he made it work in the second poorest state in the country," he said.

Schmitt said every state should have a call center for the uninsured and the insured who have no medical home. "Otherwise, who do they call? They’re boxed in," he said. "They can’t get advice from anybody."

Stateline, Copyright © 1996-2015 The Pew Charitable Trusts. All rights reserved.

Pages: 1 · 2

More Articles

- National Institutes of Health: Common Misconceptions About Vitamins and Minerals

- A Yale Medicine Doctor Explains How Naloxone, a Medication That Reverses an Opioid Overdose, Works

- Kaiser Health News Research Roundup: Pan-Coronavirus Vaccine; Long Covid; Supplemental Vitamin D; Cell Movement

- A Reminder From the White House: Prepare for New Variants As We Work to Keep Ourselves Protected Against COVID-19

- How They Did It: Tampa Bay Times Reporters Expose High Airborne Lead Levels at Florida Recycling Factory

- Secretary Antony J. Blinken: It’s Impossible Not to Be Moved by What the Ukrainians Have Achieved

- A Scout Report Selection: Science-Based Medicine

- Journalist's Resource: Religious Exemptions and Required Vaccines; Examining the Research

- Government of Canada Renews Investment in Largest Canadian Study on Aging

- Kaiser Health News: Paying Billions for Controversial Alzheimer’s Drug? How About Funding This Instead?