Bitter Primaries Hurt High-profile Candidates’ Chances in the General Election

By Clifton B. Parker

A divisive political primary that receives heavy media scrutiny reduces the party nominee’s chances in the general election, Stanford research shows.

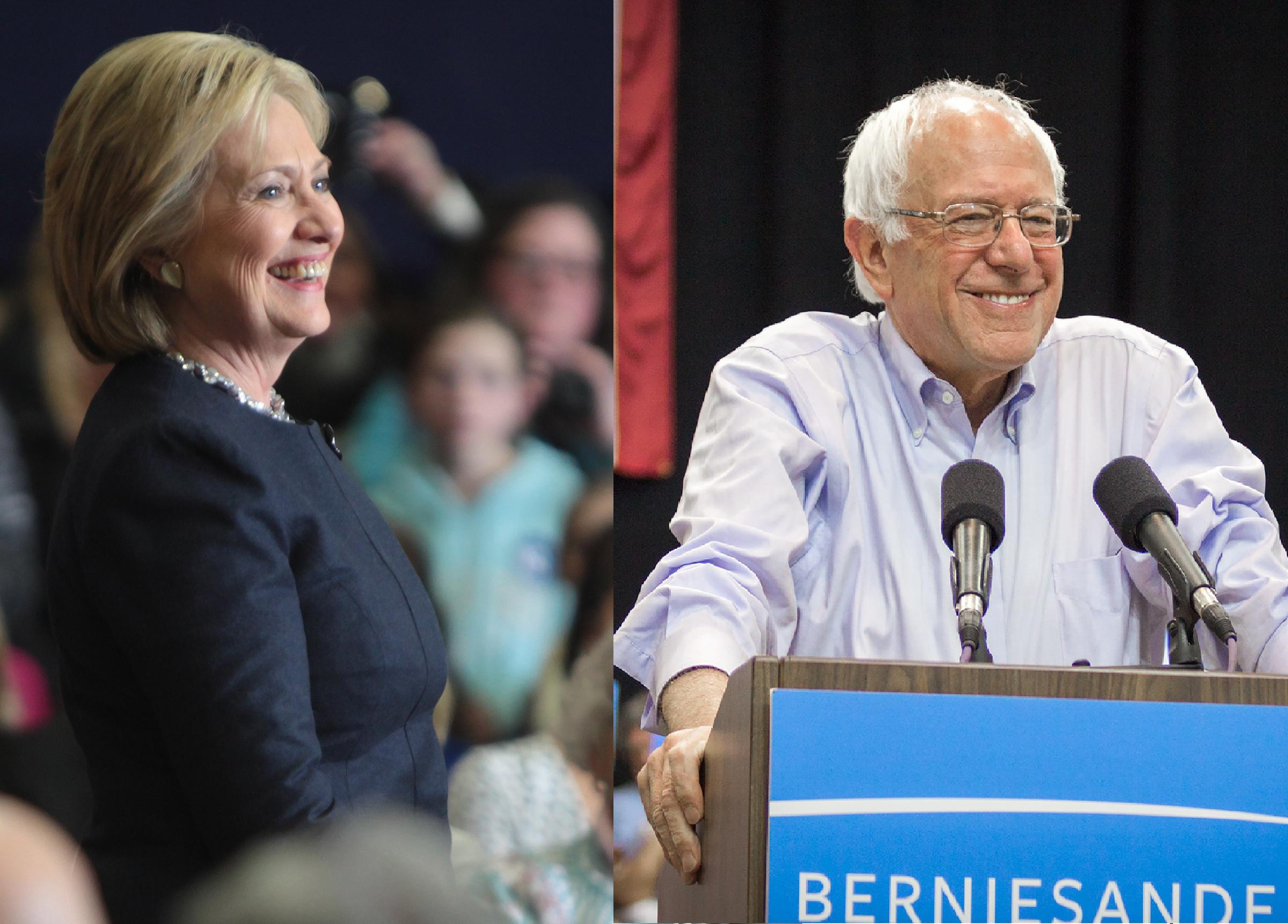

Credit: (Clinton) Gage Skidmore (Sanders) Nick Solari / Flickr; Creative Commons License

But, if the primary has not generated much attention, then the primary winner is less affected — and sometimes even helped — in the general election.

Stanford political scientist Andrew B. Hall finds that contentious primary elections can leave candidates damaged as they head into the general election.

"When parties go through divisive primaries in (highly) salient electoral settings, they suffer significant penalties in the general election," said Andrew B. Hall, an assistant professor of political science at Stanford. He recently published a study on this issue, along with co-author Alexander Fouirnaies from the University of Oxford.

Primaries involving presidential and congressional races typically attract more media coverage and voter attention compared with state legislative campaigns, Hall said. Political conventional wisdom has maintained that while highly competitive primaries may help parties select quality candidates and inform voters about them, the downside is exposing those nominees’ flaws and hurting the chance of victory in the general election.

Hall's research confirms this generally, but also explains the role of high and low media coverage as well as the degree of voter attention toward the primary campaigns.

Hall and Fouirnaies examined data from US states that use runoff primaries for party nominations. Runoffs are second-round elections that are triggered when a candidate does not win a high enough percentage of the initial primary vote, usually 50 percent. A runoff typically indicates a more contentious primary season (two rounds of voting as opposed to one) with heavier media scrutiny.

In US House and Senate races, the researchers found significant negative effects for party candidates who emerged from runoffs to advance to general elections. In fact, going to a runoff decreases the party’s general election vote share by 6 to 9 percentage points, on average, and decreases the probability that the party wins the general election by roughly 21 percentage points, on average, according to the research.

However, in US state legislative races, runoff primaries do not hurt candidates, Hall found. And, in competitive contexts, the runoff process may actually help the candidates in the general election, he said.

The difference, Hall said, is due to the nature of runoff elections in the two contexts. Typically, US House and Senate campaigns receive much more media scrutiny and attention than state legislative races.

"In the US House and US Senate, divisive primaries exert a substantial penalty on parties in the general election. Parties in high salience contexts (those with higher media coverage and voter attention) have a strong incentive to avoid publicly visible conflict among potential nominees,” he wrote.

He said that in high information contexts, making an informed choice may already be easier for voters, so open competition harms the party in the general election.

In lower information contexts, where figuring out which candidate to choose may be much more difficult for voters, parties do better in an open competition that eventually selects the stronger candidate for the general election, Hall said. Such primaries – typically state legislative races – usually receive less media coverage and voter attention is lower than for Senate or House races.

Beyond this, the researchers also found that the negative effects of runoff primaries are larger when candidates are further apart ideologically. They did not find any evidence that the runoff penalty is higher in states where the runoff primary lasts longer.

In an interview, Hall suggested that while divisive primaries may be bad for parties, they may not be bad for voters and citizens. The research indicates that divisive primaries come with a high level of information and media coverage, which suggests that the voting in such contests is more informed.

Also, commonly suggested reforms – such as eliminating primaries in favor of one general election with many candidates – come with their own problems, he added.

Pages: 1 · 2

More Articles

- Jo Freeman Writes: The 2024 Libertarian National Convention as Seen Through Feminist Eyes

- Jo Freeman Writes: Kennedy vs. Trump at the Libertarian National Convention

- Hope: A Research-based Explainer by Naseem S. Miller, The Journalist's Resource

- "The 2022 midterm election returns could ... be marred by a rush to judgment by political leaders or news outlets"* Harvard Kennedy School Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy

- Justice Department Issues Guidance on Ballot Drop Box Accessibility Requirements Under the Americans with Disabilities Act

- Voting Rights: Assistant Attorney General Kristen Clarke Testifies Before the Senate Judiciary Committee Hearing; “One of the most monumental laws in the entire history of American freedom”

- Jo Freeman Reviews Electing Madam Vice President by Nichola D. Gutgold

- Jo Freeman: Five Days in DC Where the Post-election Protests Were Puny but the Politics Were Not

- 2020 Election Wrap-Up, Women’s Congressional Policy Institute: As of press time,130 women have been elected to serve in the 117th Congress

- The Electoral College: How America Chooses Its President; They’re Really Voting for the Slate of Electors Put Forward by the Political Party their Candidate Belongs To