A Scientific Mystery: A Region of the Brain Identified, Fought Over and Rediscovered

By Amy Adams

What started a few years ago as a brain-imaging study turned into a scientific mystery that eventually ended in the basement of Stanford's Lane Medical Library, within the pages of a book first published in 1881 and last checked out in 1912.

That journey, published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, revealed the long and contentious history of an otherwise innocuous tract of nerve fibers of the visual system, running from just below to just above the ear. It also revealed the many ways scientific knowledge has been gained and lost over the centuries, and in some cases written out of history through a combination of scientific in-fighting and, at times, poor record-keeping.

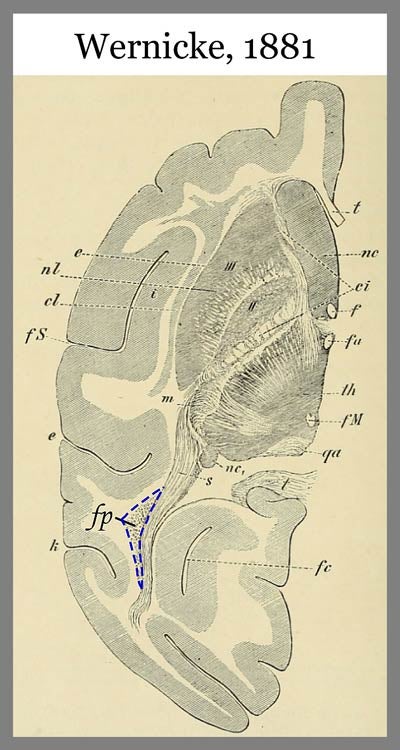

The original reference to the vertical occipital fasciculus was published by Carl Wernicke in 1881. The dashed blue lines outline where Wernicke located the region. Jason Yeatman and Kevin Weiner found the illustration in Lane Medical Library. (Courtesy of PNAS)

The journey began when then-graduate student Jason Yeatman, co-first author of the recent paper, was carrying out brain-imaging studies to better understand how kids learn to read, in the lab of Brian Wandell, a professor of psychology. Yeatman noticed that all the brain images in his study contained a structure that didn't appear in any texts.

Either he'd discovered a new brain pathway or someone else had discovered it first, but the discovery and researcher had been lost to history.

Kevin Weiner, a postdoctoral scholar and co-first author on the paper, had been working with Yeatman on the imaging studies. Weiner, who is in the lab of Kalanit Grill-Spector, associate professor of psychology, said that he had long been interested in science history, and this mystery piqued his interest.

"Jason and I decided for our own curiosity to understand what happened to this pathway," said Weiner, who is also director of public communication at the nonprofit Institute for Applied Neuroscience.

A few factors could be the cause of brain structures being discovered and forgotten. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Weiner had learned, the roughly 30,000 names of brain structures in various languages were consolidated into a list of 4,500 as part of an effort to create a universal nomenclature. "In trying to make it easier to remember names, some got written out of history," Weiner said.

In this case, consolidation wasn't the reason for the region's disappearance from the literature. The region was the source of controversy between its discoverer, Carl Wernicke, and his adviser, the influential neuroanatomist Theodor Meynert.

Pages: 1 · 2

More Articles

- National Archives Records Lay Foundation for Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI

- Nichola D. Gutgold - The Most Private Roosevelt Makes a Significant Public Contribution: Ethel Carow Roosevelt Derby

- National Institutes of Health: Common Misconceptions About Vitamins and Minerals

- Oppenheimer: July 28 UC Berkeley Panel Discussion Focuses On The Man Behind The Movie

- Julia Sneden Wrote: Love Your Library

- Scientific Energy Breakeven: Advancements in National Defense and the Future of Clean Power

- "Henry Ford Innovation Nation", a Favorite Television Show

- Center for Strategic and International Studies: “The Future Outlook with Dr. Anthony Fauci”

- Kaiser Health News Research Roundup: Pan-Coronavirus Vaccine; Long Covid; Supplemental Vitamin D; Cell Movement

- Julia Sneden Wrote: Going Forth On the Fourth After Strict Blackout Conditions and Requisitioned Gunpowder Had Been the Law